In the winter of 2019, Paris was much like any other large northern European city; messy, imperfect, and cold.

But like every other city, there was a more deliberate force behind some of the mess if you looked closely. Paris was suffering the consequences of early 00s sharing-economy optimism; Its streets jammed with Ubers, snaking around blocks of ghost hotels.

One problem in particular was uppermost in the city’s minds, and that was housing. High rises had started to appear on the edge of the city that skirted planning laws with the promise of affordable homes, only at the last minute to become holiday lets. Rents were skyrocketing, property prices fluctuating wildly, and the French authorities had had enough.

In December 2019 The French Association for Professional Tourism and Accommodation (AHTOP) took Airbnb to court, accusing them of violating the Hoguet Law. The Hoguet Law is a 51 year old piece of French legislation designed to protect renters and the wider city from unscrupulous landlords, and what transpired that day in court didn’t just set a precedent for how we regulate services, but was a glimpse into how unprepared we are for a world that relies on them.

First introduced in 1970, the Hoguet Law is just one among many that makes France one of the most heavily regulated property markets in the world. Yet despite this, in 2019 one in every 50 homes in Paris was on Airbnb. In order to operate as a property broker in France, the AHTOP argued, Airbnb should have to register as a regulated operator and conform to the same rules of renting property as everyone else.

But the European Courts of Justice thought otherwise.

Because Airbnb didn’t actually own any houses, the court argued they weren’t a real estate company. Instead, they said, Airbnb was an ‘information society service’ – meaning that they were not only exempt from any real estate laws, but any French laws at all.

Creating an international no-man’s land for services

You’d be forgiven for thinking that an ‘Information Society Service’ sounds more like a dating agency for wayward 1920’s debutantes than the description of a billion dollar property brokerage, but in Europe, Information Society Services are defined as “services normally provided for remuneration at a distance by electronic means at the individual request of the recipient of the services”. The term is an internationally recognised one, and once your service becomes one you enter a completely different word.

Free from the burdensome laws of a specific industry, or country, if your service is deemed an information society service it gets to exists in a kind of international no-mans land of regulation; able to do whatever is legal as a ‘service provider’ in the country you’re registered in, which might of course be wildly be different to the one you operate in. Importantly though, since very few countries have standards or regulations specifically aimed at services, that means you’re pretty much at liberty to do what you like.

You want to create a property booking website that inflates rental prices for local people? No problem! You want to provide insurance that’s almost impossible to claim in an emergency because you don’t have a phone line? Sure! Or perhaps you want to make it impossible to cancel a subscription by hiding in the small print? Go right ahead!

‘Information society’ was defined as a regulatory concept in the early 90s when the balance of the world started to tip from physical to digital. We needed a kind of ‘international waters’ for digital services to help the internet to become the global connector it is today. But the challenge we now have is that in 2021 a “service provided for remuneration at a distance by electronic means” could describe almost every service in existence, so long as a physical thing isn’t being bought or sold. It’s why Facebook continues to struggle to be held accountable for the content it produces, why Google can do whatever it likes, and Airbnb continues to operate in France.

But as any lawyer will tell you, laws only represent what we believe at the time we write them, and the far more worrying trend is that right now, we seem to believe we’re not responsible for a thing if we just provide a service to help people access the thing.

We live in a world unprepared for the impact of services

Being a service gives us a kind of invisibility cloak that allows us to break rules that we would usually apply to the physical world. Cars go through thousands of rounds of testing to make sure they don’t kill people, and we recall physical products for the most minor of infringements, but when a service goes wrong, somehow that is the fault of our users, how they interact with it, what they do with it.

The mid 00s/10s era of sharing economy services is a perfect example of this. How anyone expected Uber to remain an enterprise of office workers making better use of their cars on their way home from work, or Airbnb to remain a good way to save on your mortgage when you’re on holiday is almost beyond belief, but we did.

As soon as you introduce an economy to the idea of sharing, it stops being sharing and just becomes an economy, and the moment this happened was the moment those organisations decided that they were just the facilitators of an issue caused by their users. In short, they were just service providers.

Not every organization uses this invisibility deliberately, but the effect is the same nonetheless; a decision is made that has an effect on people’s lives with no thought given to the impact of that decision, simply because the thing in question is a service.

I experienced this first hand a few years ago whilst sitting in the headquarters of one of the UKs largest government departments. Twenty minutes into a relatively innocuous conversation about APIs, things took a dramatic turn. The team I was talking to got to the point they wanted to make: did I think it was ok for a service to be designed as an API first? And oh, by the way, API only.

I was shocked. The first question is one I could answer, but the second I absolutely couldn’t.

APIs of services are a good thing – they can help to lessen the burden of interacting with a service provider by allowing a user to use your service as part of another service; doing things like automatically registering new cars with DVLA as part of the the factory line process, or allowing small businesses to pay their taxes to HMRC directly through their accounting software.

In contrast, ‘API only’ would mean those users would have to interact with that service via a third-party provider. These third third-parties could choose, if they wanted, to charge for the service, to make it inaccessible or a host of other things we wouldn’t expect from a public service. An alarm bell started to jangle in my head, wasn’t this…privatisation?

I tentatively asked who had approved the idea. No elected minister or official had looked at it. No vote had been held, no public consultation had been had. I voiced my concerns and was met with frustrated confusion. What we were discussing was a purely ‘technical’ issue, why was I making such a fuss?!

Whether or not privatising this service was the right thing to do wasn’t my decision to make, but that was the point, it wasn’t the decision of anyone in that room to make. Somehow a large government organisation was proposing privatising a service with no knowledge of the fact that they were doing it.

How?!

Because this privatisation didn’t involve physical things – there were no trains, telephone poles or reservoirs to divide up, no power stations and cables to think about.

If it did, perhaps it would have been a different discussion; a years-long decision maybe, peppered with public consultations, ending with a fanfare of press releases. Certainly it would have been subject to a universal service obligation to make sure the service was open and equal to everyone. But as it was, much like airbnb this was ‘just a process’ and what we were doing to it could be classified as an insignificant technicality.

There are few professions more harmful than industrial design, service design is one of them

In 1971 Victor Papanek wrote, “There are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a few”. At the time he was right, but Papanek couldn’t have predicted that whole swathes of our cities would be unlivable, not because of poor housing, but because housing was made unaffordable by short term lets, or the roads were congested, not with cars that were badly designed, but with vast numbers of Toyota Priuses used for insta-ride-hailing. Papeneck didn’t predict the dangerous consequences of bad service design.

The biggest influences on our lives are not products – phones, cars, hoovers or even houses – they’re services, and they scale faster than any product on earth. But it is precisely *because* these organisations are service providers that don’t hold themselves accountable.

The hidden cost and impact of invisible services

The problem we have is that we don’t see services as real things. When we do, we think of them as somehow less impactful than physical things. We don’t see the harm we do with them to our users when they are badly designed, but we also don’t see how much harm these do to our organisation either.

In a 2017 financial study I and my team conducted at GDS, we discovered that 80% of the cost of the UK central government’s spending is spent on services. Not surprising really given the government is the oldest and largest service provider in the country.

What was surprising though was that up to 60% of this cost was spent answering phone calls and doing ‘casework’; essentially people calling to understand what they needed to do, or filling in a form incorrectly and being routed to a human decision maker in a caseworking team. This is the cost of bad service design. Those phone calls aren’t people who cant use digital services; 53% of them were just people checking how to do something that should have been clear and straightforward on the internet, 78% of that casework were ‘user errors’ ie. badly designed forms.

When you consider the fact that 1/3rd of UK GDP is spent on public services, that means bad service design is one of the biggest unnecessary costs to UK taxpayers. Money we’re not spending on the people and things that need it.

Yet this never made the news.

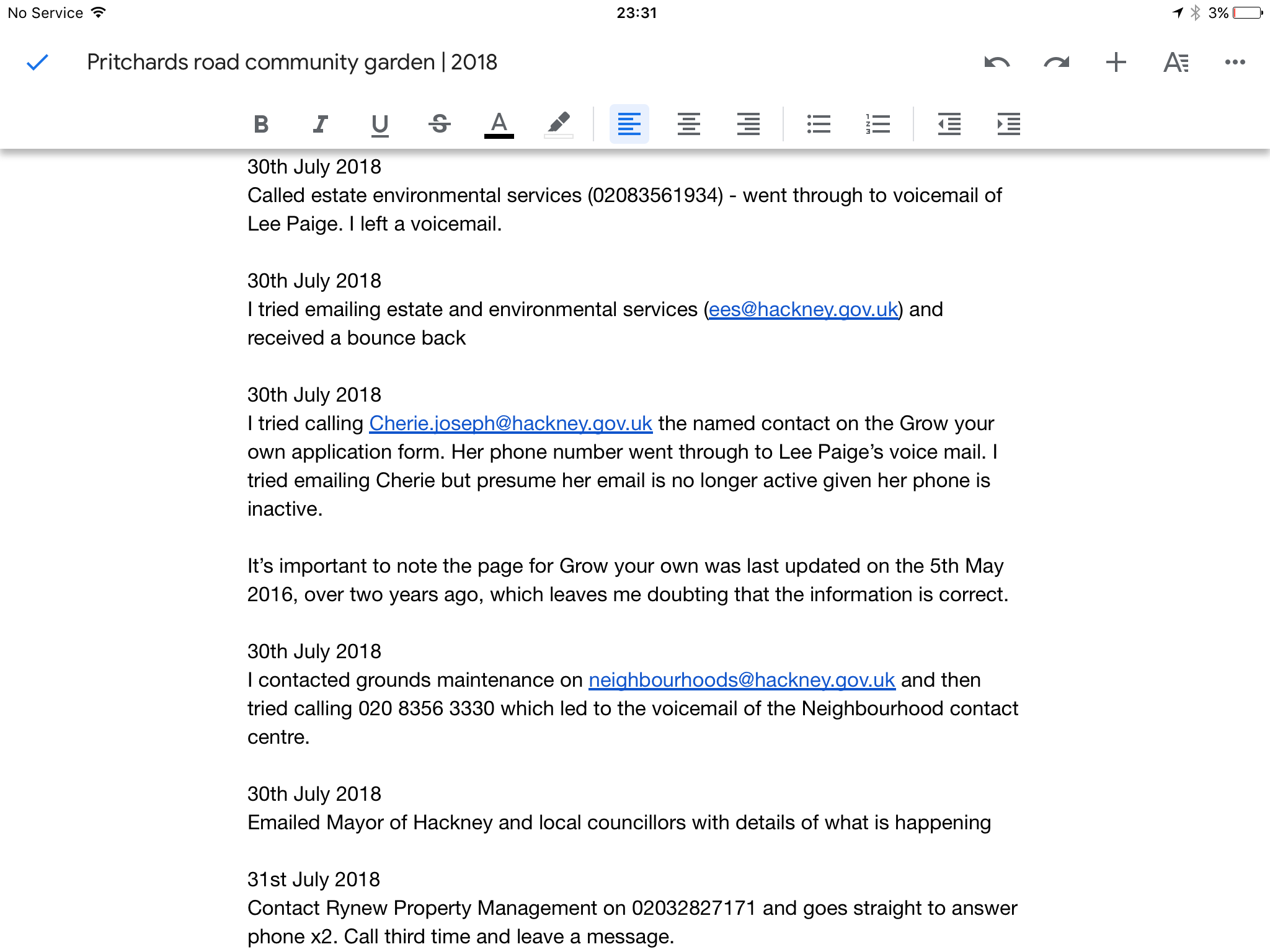

Services exist in the background by their very nature. They are the things that connect other things, the spaces between those things – like choosing a new car and having it delivered or booking an appointment at your GP and being treated for a condition. We barely notice them until we encounter something that stands out as obviously good or bad.

For the organisations that provide them, services are often barely more visible than they are for users. They require multiple people, and sometimes multiple organisations to provide all of the steps that a user needs to achieve their goal. Sometimes there are so many pieces to this puzzle, or it stretches across such a long period of time that we struggle to see them as a whole. They’re big, they’re messy, and importantly, they’re intangible, meaning their costs are hidden and so are their consequences.

The invisibility of services is both a blessing and a curse. We can continue to have the freedom to provide services with little thought of the consequences to our users (if that’s what we’re aiming for) but we won’t see the consequences to our organisation either. It’s a giant catch 22.

The medium is the message, until it’s not

Often our fist assumption when improving old services that don’t work anymore is to help that service to ‘be more digital’.

Given that many of the life-supporting services we rely on like banking, heath, food or utilities pre-date the internet, that’s a fair assumption to make. But the reality is that translating services into a new medium always poses a challenge; whether that’s moving from in-person to post, post to phone, phone to email, email to the internet or webform to chat.

The conventions of the medium often dictate the way that a service works; but the issue isn’t just our lack of understanding of the medium we’re using. The issue is that somewhere in that translation from one medium to the other, we didn’t think about what exactly we were translating – the fact that we were providing a service was lost.

Services, lost in translation

A heady euphoria for new technology takes us over. Who cares if no one can find it, have you seen what you can do with Microsoft dynamics? So what if everyone expects it to be instant when it takes two weeks, or that only being open 9-5 means no one can contact us. Just PUT IT ON THE BLOCKCHAIN!

The reality is that these issues will be issues regardless of what technology you use. No amount of new technology will make your service more findable if it’s called ‘Form V11’, and no amount of bots will hide the fact that your service isn’t open on weekends, or cuts you off if you can’t type a 14 digit card number fast enough.

The real issue we have isn’t a lack of digital literacy, or any other kind of technological literacy, but a profound lack of understanding of services – what they are, how people use them, what they need from them. Service literacy for want of a better phrase.

To get out of this situation, we need to create organisations that can see services as real, tangible things that can and should be designed, but we also need organisations that will commit to designing those services, not as an accidental byproduct of other decisions, but as a conscious, deliberate act. In short, we need organisations that are ‘service literate’; seeing services, understanding what good looks like, and committing to designing them.

Having seen 100s of organisations deal with this in the last year, there seem to be three main components to creating the kind of literacy we need in services. None are easy, but each is a vital stepping stone on the road to building good services.

The three components of service literacy

1. Seeing services

Before you can design something you have to at least acknowledge it exists, and by far the hardest part of getting any organisation to design good services is getting it to realise it has services in the first place.

Only once you’ve done that can an organisation understand that to be a service provider, you need to consciously design those services, rather than letting them happen as an accidental byproduct of other decisions in the organisation.

This is easier said than done, so organisations tend to skip to step 2 or 3 without doing this important work to help people understand services in the first palace.

How we make services visible is a whole other topic in itself so I’ll write another post on this soon.

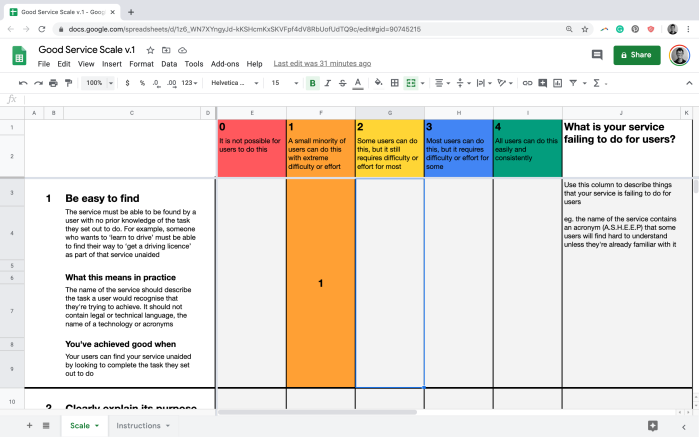

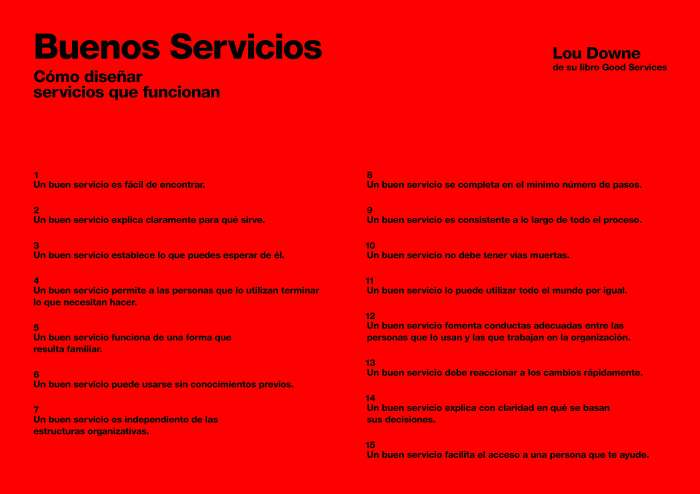

2. Understanding what makes a good service

Having a shared understanding of what makes a service good or bad is fundamental to being able to work together towards making those services we’ve just identified better.

Although we all have the same basic needs from services as users (see Good Services), when it comes to the services we provide ourselves, that knowledge often gets forgotten. We forget that we need to send confirmation emails after someone’s bought something, we forget we need to tell people how long something will take, or that our service needs to be findable by someone who hasn’t used it before.

Creating a shared sense of what is and isn’t good for your service is vital to being able to work together to make things better. If you want to read about what makes a good service and haven’t done so yet, take a look at Good Services.

3. Committing to designing services

Once you’ve understood that you’re a service provider, and then understood whether or not your services are working well, the next step is to actually commit to designing them. Crucially that doesn’t just mean words, it means committing the people, time, space and resources needed to do it.

This final hurdle can be one too many for some organisations to overcome though.

Some make it halfway, bringing in teams, but then leaving those teams without the support to make the changes they need to make, some continue to allow their services to be dictated by technology constraints, or other unconscious design decisions. Others fail to commit the people needed at all, running entire service design projects on a series of precariously balanced steering groups.

Failure to commit properly to what’s needed to deliver good services is one of the most common reasons for failure but there’s a lot more to ‘commitment’ and how that works that I can fit in here, so I’ll write another post (or series!) about this soon.